Two years ago I posted about a presentation I made to middle schoolers (seventh-graders, to be specific) on economic development.

This week I was asked to give a 15-20 minute presentation to a youth group of 14 and 15-year olds. Everyone seemed engaged, and they asked good questions. Here’s what I did.

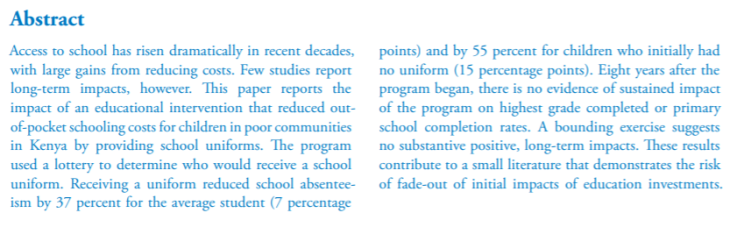

1. I showed them the world’s income distribution using relatively recent data from Pew.

2. Since it was clear I was going to focus on income — we had a short discussion of why money was important and what kinds of important things money could buy. After they shared their ideas, I listed a few, but they had already proposed many more.

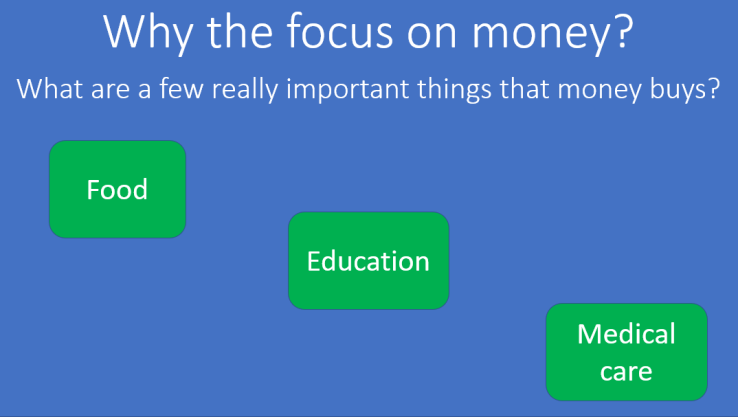

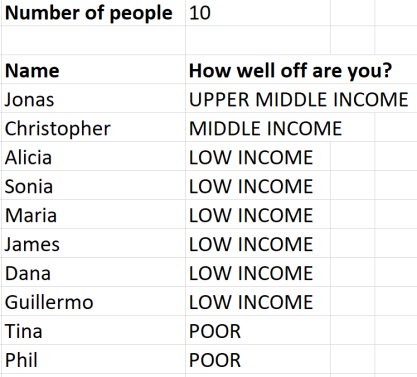

3. Based on the income distribution data, I put each person in the room somewhere in the income distribution. I opened up an Excel sheet where I could enter the number of people in the room, and I had programmed it to — as I listed the name of each person in the room — assign them to an income group so that when I finished everyone in the room, it would reflect the global income distribution.

Then, to make it a little more concrete (and fun!), I distributed chocolate based on youth’s assigned income groups. So the upper-middle income youth got a chocolate bar, the middle income people got mini chocolate bars, the low income people got Hershey’s Kisses, and the the poor person got a single Hershey’s Dot (about the size of an M&M). [I actually forgot the Kisses, but that was how it was supposed to work.] If you’re budget conscious, like I am, I was able to finance the whole thing for a few dollars at a discount store.

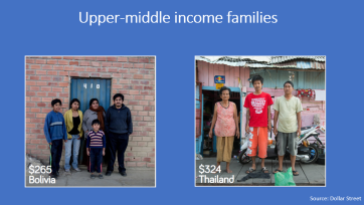

4. I showed examples — using pictures from Dollar Street — of what households in each income group might look like. We talked about the housing materials.

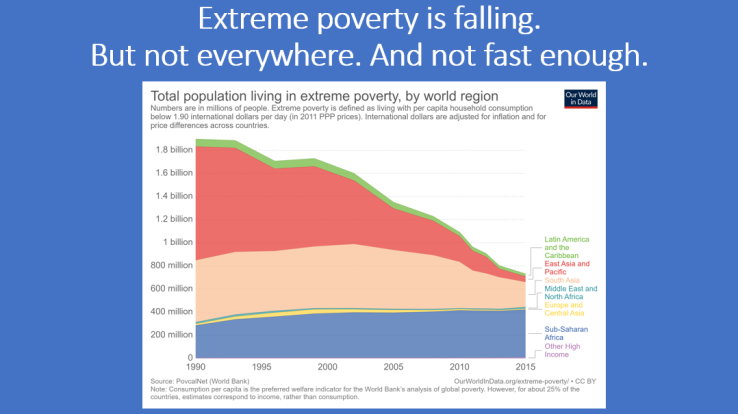

5. Extreme poverty has fallen dramatically, but there are still nearly 800 million people in the world who are extremely poor. So there’s a long way to go. (Thanks to Our World in Data for the figure!)

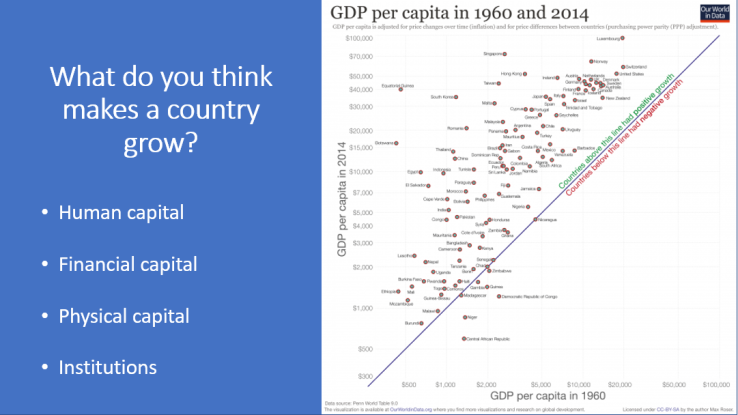

6. I talked through two sides to development economics, the macro (how can poor countries grow prosperous?) and the micro (how can poor individuals and families exit poverty and enjoy prosperity?).

7. I asked them what they think makes a country grow? After they shared some ideas, I talked briefly about four types of capital.

8. I talked about three specific projects that I’ve worked on: (a) how Rwanda can get on a rapid growth path, (b) how Tanzania can implement an effective safety net, and (c) the economic impact of the Ebola epidemic of 2014.

9. I talked a little bit about where my work has taken me. (Blue indicates conferences and seminar. Green indicates a research project or policy discussions.)

10. Finally, I talked about both my path to become a development economist, and a few of the other jobs that allow people to work in international development. Of course, there are many more! This was just to give a taste.

That’s it! It was fun. What have you done to explain these concepts to young people?

Every since Pop whipped me when I was six for running around the pen with no shoes on, I’ve never been barefoot out here again. You could get worms, Pop had said. Later that night, he told me stories about him and his sisters and brothers when they were young, playing barefoot because all they had was one pair of shoes each and them for church. They all got worms, and when they used the outhouse, they pulled worms out of their butts. I don’t tell Pop, but that was more effective than the whipping.

Every since Pop whipped me when I was six for running around the pen with no shoes on, I’ve never been barefoot out here again. You could get worms, Pop had said. Later that night, he told me stories about him and his sisters and brothers when they were young, playing barefoot because all they had was one pair of shoes each and them for church. They all got worms, and when they used the outhouse, they pulled worms out of their butts. I don’t tell Pop, but that was more effective than the whipping.