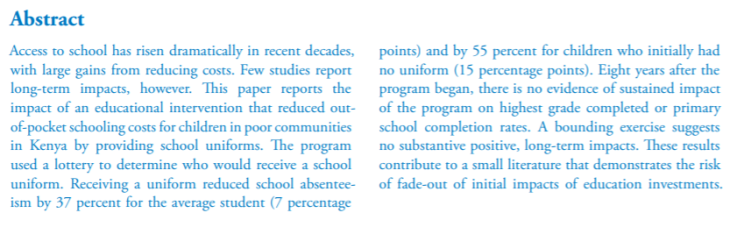

“School Costs, Short-Run Participation, and Long-Run Outcomes: Evidence from Kenya”: My paper with Mũthoni Ngatia is out as a World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Here’s what we learned.

Even though primary education is “free” in many countries, families face many incidental expenses: uniforms, transport, and materials, among others.

In Kenya, we worked with an NGO that provided free school uniforms to children to reduce the cost of schooling.

I know that you’re going to say: Do we need another study of “giving stuff” for education and how it affects attendance? Aren’t we supposed to be focused on learning and pedagogy?

First, while attending school is no guarantee of learning, it’s a really important part of the process.

Second, we follow these students over 8 years. Few international education studies trace the time path of impact.

A school uniform can increase school participation by multiple means. Families don’t have to pay for the uniforms. AND students don’t feel stigmatized by being the only kid without a uniform.

What do we find? In the short run, providing a school uniform does increase school participation.

The impacts are particularly large for the poorest kids. Absenteeism drops by 15 percentage points for them, eliminating 55 percent of absenteeism for them.

But 8 years later, the children who participated in the program had no better educational outcomes than those who did not.

Some educational interventions have long-lasting impacts: Smaller early-grade classes in the USA have translated into better college performance.

But we can’t assume it. In this case, initial gains in school participation do not translate into more school completion.

And a few last words from the paper: “Take care when interpreting short-term results, taking into account these results and others which demonstrate that long-term impacts may vary – sometimes dramatically – from initial effects.”

“Gathering long-term data is costly, but without it, the trajectory of impacts resulting from the wide range of interventions currently being implemented remains a mystery.”

That’s it! Big short-term impacts for poor kids but disappointing long-term impacts. Check out the paper!