Two years ago, Anna Popova and I put out a working paper examining whether beneficiaries of cash transfer programs are more likely than others to spend money on alcohol and cigarettes (“temptation goods”). That paper has just been published, in the journal Economic Development and Cultural Change.

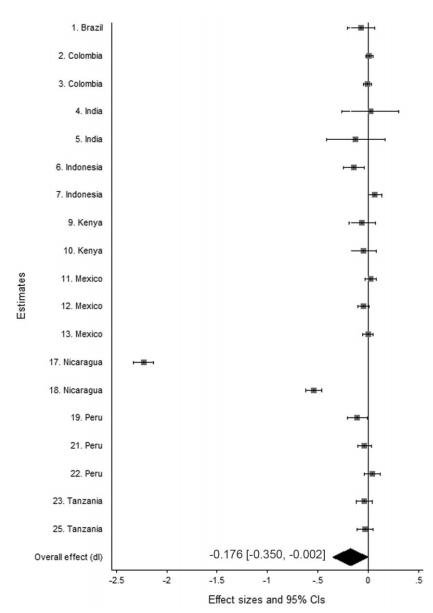

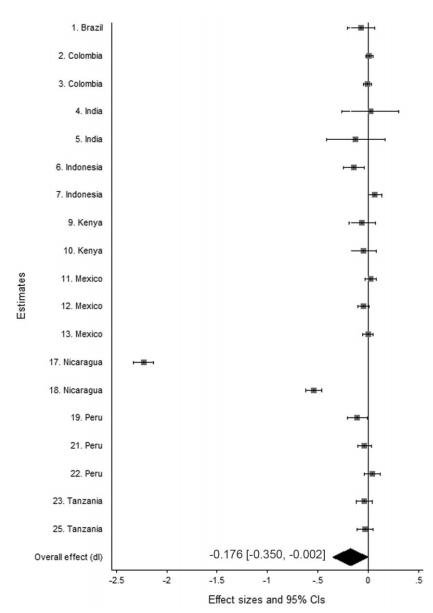

The findings of the published version do not vary from the working paper: Across continents, whether the programs have conditions or don’t, the result is the same. The poor don’t spend more on temptation goods. But for the published version, we complemented our vote count (where you sum up how many programs find a positive effect and how many find a negative effect) with a formal meta-analysis. You can see the forest plot below. (The results are not substantively different from the “vote count” review that we did in the working paper and maintain in the published version as a complement to the meta-analysis.)

As you can see, while there are only two big negative effects, both from Nicaragua, most of the effects are slightly negative, and none of them are strongly positive. We do various checks to make sure that we’re not just picking up people telling surveyors what they want to hear, and we’re confident that cannot explain the consistent lack of impact across venues.

Why might there be a negative effect? After all, if people like alcohol, we might expect them to spend more on it when they have more money. We can’t say definitively, but even unconditional transfer programs almost always come with strong messaging: Recipients hear, again and again, that this money is for their family, that this money is to make their lives better, and so on and so on. We know from others areas of economics that labeling money has an effect (called the flypaper effect).

So you can be for cash transfers or against cash transfers, but don’t be against them because you think the poor will use the money on temptation goods. They won’t. To quote the last line of our paper, “We do have estimates from Peru that beneficiaries are more likely to purchase a roasted chicken at a restaurant or some chocolates soon after receiving their transfer (Dasso and Fernandez 2013), but hopefully even the most puritanical policy maker would not begrudge the poor a piece of chocolate.”