There is an alternative to Twitter, Facebook and all those indignant op-eds that we use to confirm the superiority of our beliefs. It’s a flexible, troll-free, hacker-resistant platform on which complex social and moral questions can be carefully explored. It simultaneously engages our empathy and models the action of empathy for us. It’s called a novel.

Author: David Evans

I write it down so I don’t have to remember it

In the film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Henry Jones — Indiana’s father — finds the key information needed to safely traverse a perilous journey to retrieve the Holy Grail.

Professor Henry Jones: Well, he who finds the Grail must face the final challenge.

Indiana Jones: What final challenge?

Professor Henry Jones: Three devices of such lethal cunning.

Indiana Jones: Booby traps?

Professor Henry Jones: Oh, yes. But I found the clues that will safely take us through them in the Chronicles of St. Anselm.

Indiana Jones: [pleased] Well, what are they?

[annoyed]

Indiana Jones: Can’t you remember?

Professor Henry Jones: I wrote them down in my diary so that I wouldn’t *have* to remember.

[Dialogue is documented at IMDB.com.]

Just yesterday, I wrote to a colleague asking for information, and he pointed me to a blog post that I wrote two months ago. I often keep my research findings straight, but — to adapt from Henry Jones — I write them down so that I don’t have to remember them! As University of Chicago professor Linda Ginzel tells her students, “If you don’t write it down, it doesn’t exist.”

In honor of the senior Dr. Jones, I made this little reminder…

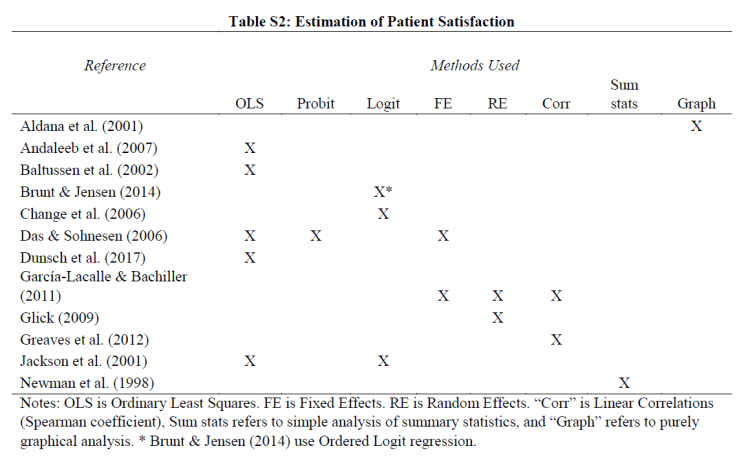

How do researchers estimate regressions with patient satisfaction at the outcome? A brief review of practice

Recently, Anna Welander Tärneberg and I were doing research with patient satisfaction as the outcome, and we checked how other researchers had estimated these equations in the past. Here is what we found, as documented in the appendix of our recently published paper in the journal Health Economics.

People use a lot of different methods, and many authors use multiple methods. But there is a rich history of using Ordinary Least Squares regressions to estimate impacts on patient satisfaction. In our paper, we used OLS but verified all the results with Probit and Logit regressions. To add to this list, Dunsch et al. (including me) have a new paper out last week on patient satisfaction in Nigeria, also using OLS as the main estimation method.

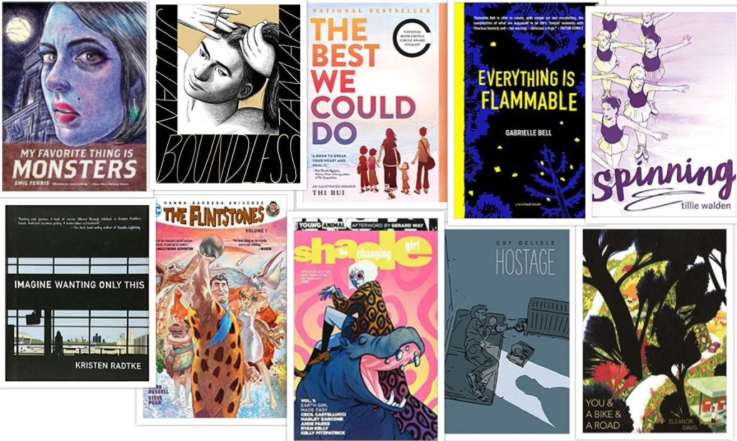

What were the best graphic books of 2017?

I’ve been reading more graphic books lately — graphic novels, graphic short stories, graphic memoirs, graphic biographies — and I’ve found that many outlets posted “best of 2017” lists.

I’ve been reading more graphic books lately — graphic novels, graphic short stories, graphic memoirs, graphic biographies — and I’ve found that many outlets posted “best of 2017” lists.

I went through 15 “best of 2017” lists and identified the 100 graphic books that were recommended between them. A total of 10 books were recommended at least 3 “best of” lists. I’ve read half of the top 10, and they really are excellent, but there are many gems deeper down the list. So don’t stop digging.

The top 10 are listed below. The full list of 100 recommendations is available here. The numbering is funny because I use the same number — such 2a and 2b — if books received the same number of recommendations.

1. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, by Ferris (recommended on 11 lists)

2a. The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir, by Bui (9 lists)

2b. Boundless, by Tamaki (9 lists)

4. Everything Is Flammable, by Bell (6 lists)

5. Hostage, by Delisle (5 lists)

6a. Imagine Only Wanting This, by Radtke (4 lists)

6b. Spinning, by Walden (4 lists)

8a. The Flintstones, Volume 1, by Russell & Pugh (3 lists)

8b. Shade the Changing Girl, Volume 1, by Castellucci & Zarcone (3 lists)

8c. You & a Bike & a Road, by Davis (3 lists)

Eight of the top ten are by women, which is cool (1, 2a, 2b, 4, 6a, 6b, 8b, and 8c).

Happy reading!

Are patients really satisfied?

Yesterday, my new paper — Bias in patient satisfaction surveys: a threat to measuring healthcare quality — was published at BMJ Global Health. It’s co-authored with Felipe Dunsch, Mario Macis, and Qiao Wang.

Here’s a quick rundown of what we learned.

Many health systems use patient satisfaction surveys to gauge one key element of health services: the patient experience. As part of evaluating an intervention to improve health care management in Nigeria, we piloted patient satisfaction questionnaires.

A common way to measure patient satisfaction is to give patients a series of statements and to ask if they agree or disagree: “The clinic was clean.” “Staff explained your condition well.” That kind of thing. We noticed that people seemed to be agreeing with everything.

Was that because the quality of care was good, or because saying yes is just easier?

So we randomly assigned some patients to get the standard statements, and others to get negatively framed statements. “The clinic was dirty.” “Staff were rude.” “Staff explained your condition poorly.”

Reframing the questions negatively led to significantly lower reports of patient satisfaction on almost every item.

Sometimes the drops were big, as high as 12 percentage points and 19 percentage points.

Our work was in Nigeria, but a lot of patient satisfaction questionnaires that we reviewed from a lot of countries use this positive framing.

But that likely gives a falsely optimistic view of the patient experience.

Patient satisfaction questionnaires that either mix positive and negative framing, or that avoid agree/disagree formats can do better.

Of course, the quality of care is much more than patient satisfaction. But good health care systems can and should offer a positive patient experience.

What I’ve been reading this month – March 2018

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality, by Angus Deaton. Deaton — winner of the 2015 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences — offers a thorough and thoughtful history of inequalities in health and wealth. Within the broader analysis lies a wealth of gems: “The familiar concept of gross domestic product (GDP) is a good place to start (though it would be a very poor place to stop).” “In truth there are no experts on what a poor family ‘needs’ — except perhaps the poor family itself.” Much of the press coverage of this book focused on Deaton’s critique of foreign aid, which is interesting (whether you agree with it or not), but it’s a minority of the book.

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality, by Angus Deaton. Deaton — winner of the 2015 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences — offers a thorough and thoughtful history of inequalities in health and wealth. Within the broader analysis lies a wealth of gems: “The familiar concept of gross domestic product (GDP) is a good place to start (though it would be a very poor place to stop).” “In truth there are no experts on what a poor family ‘needs’ — except perhaps the poor family itself.” Much of the press coverage of this book focused on Deaton’s critique of foreign aid, which is interesting (whether you agree with it or not), but it’s a minority of the book. The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir, by Thi Bui — In this graphic memoir, a Vietnamese-American woman explores her family history and what it means for her own identity. She traces her parents’ stories during the Vietnam War, her family’s migration to the U.S. when she was a child, and their subsequent life as immigrants. It’s a beautiful and powerful and difficult tale. Abraham Riesman at Vulture: “Narratively intricate, intellectually fastidious, and visually stunning.” Publisher’s Weekly: A “mélange of comedy and tragedy, family love and brokenness.”

The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir, by Thi Bui — In this graphic memoir, a Vietnamese-American woman explores her family history and what it means for her own identity. She traces her parents’ stories during the Vietnam War, her family’s migration to the U.S. when she was a child, and their subsequent life as immigrants. It’s a beautiful and powerful and difficult tale. Abraham Riesman at Vulture: “Narratively intricate, intellectually fastidious, and visually stunning.” Publisher’s Weekly: A “mélange of comedy and tragedy, family love and brokenness.” The Undoing Project: A Friendship that Changed Our Minds, by Michael Lewis — This is the fascinating story of an exceptional research collaboration that spanned decades, together with the resultant breakthroughs in psychology, with significant spillovers into economics and many other fields. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky were pioneers in rethinking how we should think about how people think. Sunstein & Thaler in the New Yorker: Lewis tells “fascinating stories about intriguing people” and leaves “readers to make their own judgments about what lessons should be learned.” One great quote in the book — from Amos Tversky — points to an attribution problem that raises its head in development work constantly: “It is sometimes easier to make the world a better place than to prove you have made the world a better place.”

The Undoing Project: A Friendship that Changed Our Minds, by Michael Lewis — This is the fascinating story of an exceptional research collaboration that spanned decades, together with the resultant breakthroughs in psychology, with significant spillovers into economics and many other fields. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky were pioneers in rethinking how we should think about how people think. Sunstein & Thaler in the New Yorker: Lewis tells “fascinating stories about intriguing people” and leaves “readers to make their own judgments about what lessons should be learned.” One great quote in the book — from Amos Tversky — points to an attribution problem that raises its head in development work constantly: “It is sometimes easier to make the world a better place than to prove you have made the world a better place.” Boundless, by Jillian Tamaki — This wonderfully weird collection of short stories in comic format ends mid-word, fittingly. The most original and intriguing graphic work I remember reading. Michael Cavna in the Washington Post: “Organically disorienting, visually jarring — and, sometimes, sublime.” Rachel Cooke in the Guardian: “Fleeting as they are – most [of the stories] can be read in as long as it takes to order and receive a latte – each one is as indelible as it is singular.”

Boundless, by Jillian Tamaki — This wonderfully weird collection of short stories in comic format ends mid-word, fittingly. The most original and intriguing graphic work I remember reading. Michael Cavna in the Washington Post: “Organically disorienting, visually jarring — and, sometimes, sublime.” Rachel Cooke in the Guardian: “Fleeting as they are – most [of the stories] can be read in as long as it takes to order and receive a latte – each one is as indelible as it is singular.” Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction, by Grady Hendrix with Will Errickson — I don’t read horror fiction. When I was a teenager I read some Stephen King; that’s about it. But the genre experienced a heyday in the 70s and 80s, and Hendrix and Errickson document it in this entertaining cultural history. We stroll through the variety of sub-genres (possessed animals; crazy clowns; haunted houses). Hendrix and Errickson pay special attention to cover art, which is often innovative and just-as-often absurd. While many (or most) of the books he describes sound objectively pretty bad, they still testify to the boundless imagination of the authorial race. For example, here’s a roadmap through horror novels about bad kids: “Why do children act out? They might be nature creatures (Nursery Tale, Strange Seed), possessed by a vengeful spirit (Judgment Day), covering up a murder (The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane), or plotting a murder (Harriet Said…). Maybe they’re an ape-human hybrid (The Sendai), getting attacked by snakes (The Accursed), a hammer-wielding hellion (Mama’s Little Girl), capable of raising the dead (The Savior), or juggling a second personality that’s probably a demon (Smart as the Devil).” Below are a few of the covers featured in the book, in case you need more enticement.

Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction, by Grady Hendrix with Will Errickson — I don’t read horror fiction. When I was a teenager I read some Stephen King; that’s about it. But the genre experienced a heyday in the 70s and 80s, and Hendrix and Errickson document it in this entertaining cultural history. We stroll through the variety of sub-genres (possessed animals; crazy clowns; haunted houses). Hendrix and Errickson pay special attention to cover art, which is often innovative and just-as-often absurd. While many (or most) of the books he describes sound objectively pretty bad, they still testify to the boundless imagination of the authorial race. For example, here’s a roadmap through horror novels about bad kids: “Why do children act out? They might be nature creatures (Nursery Tale, Strange Seed), possessed by a vengeful spirit (Judgment Day), covering up a murder (The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane), or plotting a murder (Harriet Said…). Maybe they’re an ape-human hybrid (The Sendai), getting attacked by snakes (The Accursed), a hammer-wielding hellion (Mama’s Little Girl), capable of raising the dead (The Savior), or juggling a second personality that’s probably a demon (Smart as the Devil).” Below are a few of the covers featured in the book, in case you need more enticement.

Sourdough, by Robin Sloan — Robin Sloan is back! A few years ago he wrote a delightful debut novel — Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore — and I’ve been excited to get to this, his new novel. Jason Sheehan at NPR put it well: “Robin Sloan’s new novel, Sourdough, is exactly like his first book, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, except that it’s not about books (exactly), but is absolutely about San Francisco, geeks, nerds, coders, secret societies, bizarrely low-impact conspiracies that solely concern single-noun obsessives (food, in this case, rather than books), and also robots. And books, too, actually, now that I think about it.” It also involves a magical sourdough starter and warring colonies of microbes. It’s great fun.

Sourdough, by Robin Sloan — Robin Sloan is back! A few years ago he wrote a delightful debut novel — Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore — and I’ve been excited to get to this, his new novel. Jason Sheehan at NPR put it well: “Robin Sloan’s new novel, Sourdough, is exactly like his first book, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, except that it’s not about books (exactly), but is absolutely about San Francisco, geeks, nerds, coders, secret societies, bizarrely low-impact conspiracies that solely concern single-noun obsessives (food, in this case, rather than books), and also robots. And books, too, actually, now that I think about it.” It also involves a magical sourdough starter and warring colonies of microbes. It’s great fun. Baking Cakes in Kigali, by Gaile Parkin — Angel Tungaraza is a Tanzanian woman who has moved to Rwanda with her family and started a cake-baking business. She meets lots of interesting people and has interesting conversations with them. The novel is reminiscent of The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency in that it tries to say something about current issues while not really focusing on plot and not having any serious conflict. The World Bank and the IMF both appear, with unflattering characterizations. And one exchange about the source of motivation for development workers inspired one of my recent blog posts: “Perhaps these big organisations needed to pay big salaries if they wanted to attract the right kind of people; but Sophie had said that they were the wrong kind of people if they would not do the work for less. Ultimately they had concluded that the desire to make the world a better place was not something that belonged in a person’s pocket. No, it belonged in a person’s heart.”

Baking Cakes in Kigali, by Gaile Parkin — Angel Tungaraza is a Tanzanian woman who has moved to Rwanda with her family and started a cake-baking business. She meets lots of interesting people and has interesting conversations with them. The novel is reminiscent of The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency in that it tries to say something about current issues while not really focusing on plot and not having any serious conflict. The World Bank and the IMF both appear, with unflattering characterizations. And one exchange about the source of motivation for development workers inspired one of my recent blog posts: “Perhaps these big organisations needed to pay big salaries if they wanted to attract the right kind of people; but Sophie had said that they were the wrong kind of people if they would not do the work for less. Ultimately they had concluded that the desire to make the world a better place was not something that belonged in a person’s pocket. No, it belonged in a person’s heart.” Never Let You Go, by Chevy Stevens — Thriller! Set in British Columbia! About a women, her daughter, and her recently-released-from-prison abusive ex-husband. Exciting! I did not predict the ending.

Never Let You Go, by Chevy Stevens — Thriller! Set in British Columbia! About a women, her daughter, and her recently-released-from-prison abusive ex-husband. Exciting! I did not predict the ending. fan fiction author Cather over the course of her first year in college. I loved her writing professor and wish we’d seen more of her. I’ve never read any fan fiction (except a couple of pages of 50 Shades of Grey — which originated as Twilight fan fiction — over someone’s shoulder on the metro), but Cather’s sentiments are deeply relatable: “Maybe you think I’m a little crazy, but I only ever let people see the tip of my crazy iceberg. Underneath this veneer of slightly crazy and socially inept, I’m a complete disaster.”

fan fiction author Cather over the course of her first year in college. I loved her writing professor and wish we’d seen more of her. I’ve never read any fan fiction (except a couple of pages of 50 Shades of Grey — which originated as Twilight fan fiction — over someone’s shoulder on the metro), but Cather’s sentiments are deeply relatable: “Maybe you think I’m a little crazy, but I only ever let people see the tip of my crazy iceberg. Underneath this veneer of slightly crazy and socially inept, I’m a complete disaster.” Hilo Book 4: Waking the Monsters, by Judd Winick — Girl’s mom wants her to be a cheerleader; she wants to be a ninja wizard instead. Robots! Aliens! So much awesomeness! Can’t wait for book 5! I love reading these with my kids.

Hilo Book 4: Waking the Monsters, by Judd Winick — Girl’s mom wants her to be a cheerleader; she wants to be a ninja wizard instead. Robots! Aliens! So much awesomeness! Can’t wait for book 5! I love reading these with my kids.How to pass French without knowing French…

…at the University of Michigan in the 1960s, anyway.

Michigan required that all PhD students in psychology pass a proficiency test in two foreign languages… [Amos Tversky] picked French. The test was to translate three pages from a book in the language: The student chose the book, and the tester chose the pages to translate. Amos went to the library and dug out a French math textbook with nothing but equations in it… The University of Michigan declared Amos Tversky proficient in French.

from Michael Lewis’s The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds.

How Angus Deaton thinks you can make the world a better place

When Princeton students come to talk with me, bringing their deep moral commitment to helping make the world a better, richer place, it is these ideas that I like to discuss, steering them away from plans to tithe from their future incomes, and from using their often formidable talents of persuasion to increase the amounts of foreign aid. I tell them to work on and within their own governments, persuading them to stop policies that hurt poor people, and to support international policies that make globalization work for poor people, not against them.

This is (almost) the end of Deaton’s book The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. This counsel reminds me of the Commitment to Development Index, which shows that there are many policies that rich countries can enact to help the poor beyond their borders besides providing foreign aid, such as easier migration rules and lower tariffs.

Can Big Data Point Us Towards Faster, Higher-Impact Scientific Discoveries?

How can the process of science be better? How can we move faster towards groundbreaking scientific discoveries? In Science magazine, Fortunato et al. write about what large-scale data analysis tells us about the science of doing science. (They call it the Science of Science, or SciSci.)

There is more data available than ever before – “from research funding, productivity, and collaboration to paper citations and scientist mobility” – and that, combined with methods that emerge from collaborations among different kinds of scientists (including the social kind), allows the study of what drives science.

Here are a few findings that struck me:

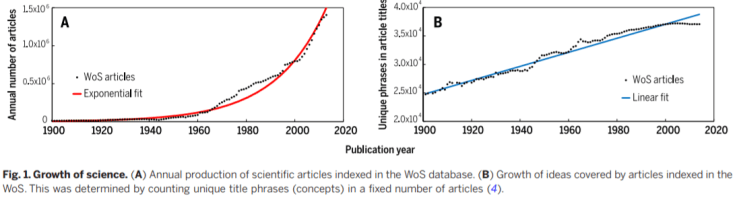

- Lots of science, with more every year! The amount of scientific research has grown exponentially, and the number of new ideas in scientific research has also grown dramatically (but not exponentially).

Source: Fortunato et al. 2018

- Most scientists are conservative in their research. Scientists tend to do research on the areas of their expertise. “Although an innovative publication tends to result in higher impact than a conservative one, high-risk innovation strategies are rare, because the additional reward does not compensate for the risk of failure to publish at all.” But those conservative strategies “serve individual careers well but are less effective for science as a whole.”

- Interdisciplinarity yields big gains in impact, but not in funding. “The successful combination of previously disconnected ideas and resources that is fundamental to interdisciplinary research often violates expectations and leads to novel ideas with high impact.” But “truly novel or interdisciplinary” grant applications tend to earn lower scores from expert evaluators. The highest impact science is a mix of old and new, “primarily grounded in conventional combinations of prior work, yet it simultaneously features unusual combinations.”

- It’s the scientist that creates impact, not the university. “When examining changes in impact associated with each move [by scientists across institutions] as quantified by citations, no systematic increase or decrease was found, not even when scientists moved to an institution of considerably higher or lower rank.”

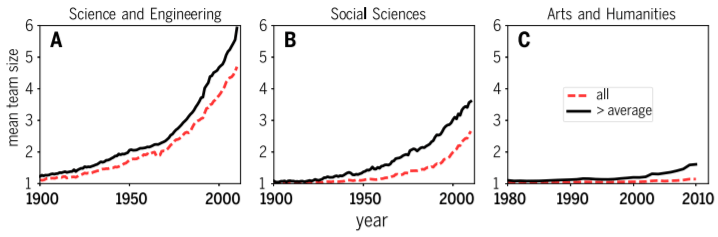

- Collaboration yields impact. “Nowadays, a team-authored paper in science and engineering is 6.3 times more likely to receive 1000 citations or more than a solo-authored paper, a difference that cannot be explained by self-citations.” One possible explanation is #3 above. As you can see in the figure below, the above-average cited papers (black line) are those with larger teams than average (red line).

Source: Fortunato et al. 2018

- Who gets credit for a multi-authored paper? “Most credit will go to the coauthors with the most consistent track record in the domain of the publication.”

There’s much more in the review article; I recommend it. But here’s a last word from the authors on how to think about the impact of scientific research: “Science often behaves like an economic system with a one-dimensional ‘currency’ of citation counts. This creates a hierarchical system, in which the ‘rich-get-richer’ dynamics suppress the spread of new ideas, particularly those from junior scientists and those who do not fit within the paradigms supported by specific fields. Science can be improved by broadening the number and range of performance indicators.”

Disclosure: One of the authors of Fortunato et al. is my brother James Evans.

What I’ve been reading this month

What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky, by Lesley Nneka Arimah — A breathtaking collection of stories. The prose is beautiful; it made other books I read or listened to at the same time seem pedestrian. Some of the stories are realistic, others incorporate magical realism. Some take place in Nigeria, others in the U.S., other in both. I’d read a novel by Arimah on any of these stories. One woman observes about her boyfriend: “He didn’t seem to mind how joy had become a finite meal she begrudged seeing anyone but herself consume.” Or a father comments on his daughter: “He should chastise the girl, he knows that, but she is his brightest ember and he would not have her dimmed.” As Marina Warner wrote in the New York Times, “It would be wrong not to hail Arimah’s exhilarating originality: She is conducting adventures in narrative on her own terms, keeping her streak of light, that bright ember, burning fiercely, undimmed.”

What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky, by Lesley Nneka Arimah — A breathtaking collection of stories. The prose is beautiful; it made other books I read or listened to at the same time seem pedestrian. Some of the stories are realistic, others incorporate magical realism. Some take place in Nigeria, others in the U.S., other in both. I’d read a novel by Arimah on any of these stories. One woman observes about her boyfriend: “He didn’t seem to mind how joy had become a finite meal she begrudged seeing anyone but herself consume.” Or a father comments on his daughter: “He should chastise the girl, he knows that, but she is his brightest ember and he would not have her dimmed.” As Marina Warner wrote in the New York Times, “It would be wrong not to hail Arimah’s exhilarating originality: She is conducting adventures in narrative on her own terms, keeping her streak of light, that bright ember, burning fiercely, undimmed.” Economism: Bad Economics and the Rise of Inequality, by James Kwak — Kwak walks through how a number of simplistic economic models break down in the face of empirical evidence — e.g., the minimum wage, health care markets, the pay of chief executives — and yet a religious adherence to these Economics 101 models often serves to advance the interests of the rich. This is what he calls economism, a “misleading caricature of economic knowledge.” Martin Sandbu wrote in the Financial Times, “Kwak’s book is didactic in the best possible way, and it proves beyond doubt how dangerous a little knowledge can be.” Not an indictment of economics but rather of its misuses.

Economism: Bad Economics and the Rise of Inequality, by James Kwak — Kwak walks through how a number of simplistic economic models break down in the face of empirical evidence — e.g., the minimum wage, health care markets, the pay of chief executives — and yet a religious adherence to these Economics 101 models often serves to advance the interests of the rich. This is what he calls economism, a “misleading caricature of economic knowledge.” Martin Sandbu wrote in the Financial Times, “Kwak’s book is didactic in the best possible way, and it proves beyond doubt how dangerous a little knowledge can be.” Not an indictment of economics but rather of its misuses. Taduno’s Song, by Odafe Atogun — A music superstar – Taduno – who has used his music against a Nigerian dictator returns home after a few months in exile to find that no one remembers him. He has to unravel the mystery and seek to rescue his girlfriend, who has been kidnapped by government forces. Of the premise, one character said, “It all sounds so complicated and strange.” Yes, but also beautiful. The simplicity of Atogun’s prose let me read almost the entire book on one long flight (Addis Ababa – Washington, DC). Taduno reminds us, “When music is silent you hear the laughter of the tyrant.” As George Shankar wrote in the FT, Atogun’s “simple prose lends the narrative a gentle urgency… A powerful, lingering fable.”

Taduno’s Song, by Odafe Atogun — A music superstar – Taduno – who has used his music against a Nigerian dictator returns home after a few months in exile to find that no one remembers him. He has to unravel the mystery and seek to rescue his girlfriend, who has been kidnapped by government forces. Of the premise, one character said, “It all sounds so complicated and strange.” Yes, but also beautiful. The simplicity of Atogun’s prose let me read almost the entire book on one long flight (Addis Ababa – Washington, DC). Taduno reminds us, “When music is silent you hear the laughter of the tyrant.” As George Shankar wrote in the FT, Atogun’s “simple prose lends the narrative a gentle urgency… A powerful, lingering fable.” Browse: The World in Bookshops, edited by Henry Hitchings — I love bookshops, and I’ve enjoyed exploring the offerings from open market book stalls in Dar es Salaam to a piled-high dolly of books on the sidewalk in Addis Ababa, to proper brick-and-morter bookshops in Rio de Janeiro, Kigali, and Mexico City. In this delightful, creative collection, authors from India, China, Turkey, Colombia, Kenya, the U.K., Denmark, Italy, Germany, the Ukraine, and the U.S. reflect on the role of bookshops — used and new — in their lives. In his essay on bookshops in Bogotá, Colombia, Juan Gabriel Vasquez writes “A good bookshop is a place we go into looking for a book and come out of with one we didn’t know existed. That’s how the literary conversation gets widened and that’s how we push the frontiers of our experience, rebelling against its limits.” This reminds me of sociologist James Evans’s work on how the shift to electronic journals led to a narrowing of citations: “By drawing researchers through unrelated articles, print browsing and perusal may have facilitated broader comparisons and led researchers into the past.”

Browse: The World in Bookshops, edited by Henry Hitchings — I love bookshops, and I’ve enjoyed exploring the offerings from open market book stalls in Dar es Salaam to a piled-high dolly of books on the sidewalk in Addis Ababa, to proper brick-and-morter bookshops in Rio de Janeiro, Kigali, and Mexico City. In this delightful, creative collection, authors from India, China, Turkey, Colombia, Kenya, the U.K., Denmark, Italy, Germany, the Ukraine, and the U.S. reflect on the role of bookshops — used and new — in their lives. In his essay on bookshops in Bogotá, Colombia, Juan Gabriel Vasquez writes “A good bookshop is a place we go into looking for a book and come out of with one we didn’t know existed. That’s how the literary conversation gets widened and that’s how we push the frontiers of our experience, rebelling against its limits.” This reminds me of sociologist James Evans’s work on how the shift to electronic journals led to a narrowing of citations: “By drawing researchers through unrelated articles, print browsing and perusal may have facilitated broader comparisons and led researchers into the past.” Binti, by Nnedi Okorafor — Binti leaves her home in Nigeria to attend a university across the galaxy, where only 5 percent of the students are human. (It’s a nice corrective to the Star Trek universe, where humans remain remarkably dominant.) On the way, her ship is attacked, and Binti must try to save her life. Okorafor creates cultures and worlds that deeply value knowledge. (In her book Akata Witch, students who learn new magic are rewarded with currency raining down on them.) In Binti’s tribe, some are born with the “gift of mathematical sight”: and Binti uses equations to calm herself (“my mind cleared as the equations flew through it”) and to wield power. This fast-paced, 90-page novella is a quick, easy introduction to a great contemporary writer of science fiction and fantasy.

Binti, by Nnedi Okorafor — Binti leaves her home in Nigeria to attend a university across the galaxy, where only 5 percent of the students are human. (It’s a nice corrective to the Star Trek universe, where humans remain remarkably dominant.) On the way, her ship is attacked, and Binti must try to save her life. Okorafor creates cultures and worlds that deeply value knowledge. (In her book Akata Witch, students who learn new magic are rewarded with currency raining down on them.) In Binti’s tribe, some are born with the “gift of mathematical sight”: and Binti uses equations to calm herself (“my mind cleared as the equations flew through it”) and to wield power. This fast-paced, 90-page novella is a quick, easy introduction to a great contemporary writer of science fiction and fantasy. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters – Volume 1, by Emil Ferris — The protagonist of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters would rather imagine herself a monster than admit certain truths about herself. Growing up in Chicago in the 1970s (??), she escapes into horror comics and tries to solve the mystery of her neighbor’s demise. But that description doesn’t do it justice. I found this book kind of astonishing — the depth of adolescent feeling, the sprawling art, at times pulpy and at other times subdued, the exciting story. I can’t wait for Volume 2. (The author’s story is as compelling as the book. Dana Jennings tells it well in the New York Times.)

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters – Volume 1, by Emil Ferris — The protagonist of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters would rather imagine herself a monster than admit certain truths about herself. Growing up in Chicago in the 1970s (??), she escapes into horror comics and tries to solve the mystery of her neighbor’s demise. But that description doesn’t do it justice. I found this book kind of astonishing — the depth of adolescent feeling, the sprawling art, at times pulpy and at other times subdued, the exciting story. I can’t wait for Volume 2. (The author’s story is as compelling as the book. Dana Jennings tells it well in the New York Times.) I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban, by Malala Yousafzai with Christina Lamb — Many people know that Malala Yousafzai is an education activist, shot by the Taliban, and eventual winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. This compelling memoir gives an example of passionate activism at great personal sacrifice, at the same time demonstrating the uncertainty and fear around living in an area suffused with violence. “One child, one teacher, one book and one pen can change the world.” This is the kind of book that makes you ask, “What have I been doing with my life?” in the best of ways.

I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban, by Malala Yousafzai with Christina Lamb — Many people know that Malala Yousafzai is an education activist, shot by the Taliban, and eventual winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. This compelling memoir gives an example of passionate activism at great personal sacrifice, at the same time demonstrating the uncertainty and fear around living in an area suffused with violence. “One child, one teacher, one book and one pen can change the world.” This is the kind of book that makes you ask, “What have I been doing with my life?” in the best of ways. Hostage, by Guy Delisle (translated by Helge Dascher) — In 1997, Christophe Andre was kidnapped from the Doctors Without Borders office where he was working in Russia. He was held for ransom, and Delisle tells his story through this taut graphic novel, which is excruciating in the best way, as we follow the Andre’s thoughts and his efforts to escape. “What gives ‘Hostage’ its most resonant power is not the rush of action but rather the attention to minute detail over the hundreds of pages of relative inaction” (Michael Cavna). I also really enjoyed Delisle’s graphic memoir of his time living in Pyongyang, North Korea.

Hostage, by Guy Delisle (translated by Helge Dascher) — In 1997, Christophe Andre was kidnapped from the Doctors Without Borders office where he was working in Russia. He was held for ransom, and Delisle tells his story through this taut graphic novel, which is excruciating in the best way, as we follow the Andre’s thoughts and his efforts to escape. “What gives ‘Hostage’ its most resonant power is not the rush of action but rather the attention to minute detail over the hundreds of pages of relative inaction” (Michael Cavna). I also really enjoyed Delisle’s graphic memoir of his time living in Pyongyang, North Korea. Gratitude, by Oliver Sacks — You may know Sacks as the neuroscientist cum storyteller who brought us Awakenings (made into a movie with Robin Williams and Robert De Niro), and many other books. This quartet of essays, published as a book posthumously, discusses work and love and rest. The audiobook is a contemplative 35 minutes long. “Perhaps, with luck, I will make it, more or less intact, for another few years and be granted the liberty to continue to love and to work, the two most important things, Feud insisted, in life.”

Gratitude, by Oliver Sacks — You may know Sacks as the neuroscientist cum storyteller who brought us Awakenings (made into a movie with Robin Williams and Robert De Niro), and many other books. This quartet of essays, published as a book posthumously, discusses work and love and rest. The audiobook is a contemplative 35 minutes long. “Perhaps, with luck, I will make it, more or less intact, for another few years and be granted the liberty to continue to love and to work, the two most important things, Feud insisted, in life.” African Kaiser: General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918, by Robert Gaudi — I knew little of World War I in Africa, and I still feel like I know little. The book relies heavily on accounts from British soldier Richard Meinertzhagen, who seems to have fabricated many of his tales. These tales are included here, with the justification being that they “have the ring of truth.” Separately, the heavy Eurocentrism seems out of place for a book published in 2017: I can count the named Africans in the book on one hand (maybe a six-fingered hand, like Count Rugen in The Princess Bride). And I have little patience for a book with lines like “Tom von Prince, more savage than the savages he fought…” I did enjoy learning about how the Germans and the British would read each other’s captured fiction: “Von Lettow and the Germans, however, were disappointed in the quality of the literature they captured from their enemies from time to time during the war — most cheap detective fiction from the English.” Michael Dirda of the Washington Post loved this book; Allan Mallinson in the Spectator not so much: “Gaudi’s book is so error-strewn that it would fail to qualify even as historical fiction.”

African Kaiser: General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918, by Robert Gaudi — I knew little of World War I in Africa, and I still feel like I know little. The book relies heavily on accounts from British soldier Richard Meinertzhagen, who seems to have fabricated many of his tales. These tales are included here, with the justification being that they “have the ring of truth.” Separately, the heavy Eurocentrism seems out of place for a book published in 2017: I can count the named Africans in the book on one hand (maybe a six-fingered hand, like Count Rugen in The Princess Bride). And I have little patience for a book with lines like “Tom von Prince, more savage than the savages he fought…” I did enjoy learning about how the Germans and the British would read each other’s captured fiction: “Von Lettow and the Germans, however, were disappointed in the quality of the literature they captured from their enemies from time to time during the war — most cheap detective fiction from the English.” Michael Dirda of the Washington Post loved this book; Allan Mallinson in the Spectator not so much: “Gaudi’s book is so error-strewn that it would fail to qualify even as historical fiction.” The Maze Runner, by James Dashner — Kids trapped in an artificial environment, battling to survive. Pedestrian prose, and I feel no compulsion to find out what happens next. (Maybe one of my kids will tell me.) I feel like I’d have really liked this if it had been written with a strong female protagonist, preferably with archery skills. (I loved The Hunger Games — the whole series, but especially the first book.)

The Maze Runner, by James Dashner — Kids trapped in an artificial environment, battling to survive. Pedestrian prose, and I feel no compulsion to find out what happens next. (Maybe one of my kids will tell me.) I feel like I’d have really liked this if it had been written with a strong female protagonist, preferably with archery skills. (I loved The Hunger Games — the whole series, but especially the first book.) Brave, by Svetlana Chmakova — This graphic novel is a wonderful treatment of bullying (even among “friends”). It’s technically a sequel to Chmakova’s Awkward (which I wrote about last month and also loved) but it can be read as a stand-alone.

Brave, by Svetlana Chmakova — This graphic novel is a wonderful treatment of bullying (even among “friends”). It’s technically a sequel to Chmakova’s Awkward (which I wrote about last month and also loved) but it can be read as a stand-alone.