Dawit Gebremichael Habte grew up in rural Eritrea, then Asmara (Eritrea’s capital). As a teenager he traveled through Ethiopia and entered Kenya as a refugee from the Ethiopia-Eritrea conflict. Ultimately he migrated to the United States, studied at Johns Hopkins University, and went to work for Michael Bloomberg’s company. But he didn’t do it alone! Early in his memoir, Habte quotes an Eritrean proverb: “To those who have done you favors, either return the favor or tell others about their good deeds.” Habte’s memoir — Gratitude in Low Voices — is focused on gratitude to all those who helped him on his path. Along the way, he shares his experience of both rural and urban life in Eritrea, a short history of Eritrea and of the long-term conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea: “Out of the fifty-three former European colonies in Africa, Eritrea was the only country to be denied independence after its European masters departed.” His escape to Kenya is harrowing, and when he arrives in the U.S. — like many other refugees — the challenges are far from over. But I enjoyed Habte’s story. He gives brief bios of many of the people who helped him along the way as a way of honoring, which interrupts his narrative, but I respect his objective.

Dawit Gebremichael Habte grew up in rural Eritrea, then Asmara (Eritrea’s capital). As a teenager he traveled through Ethiopia and entered Kenya as a refugee from the Ethiopia-Eritrea conflict. Ultimately he migrated to the United States, studied at Johns Hopkins University, and went to work for Michael Bloomberg’s company. But he didn’t do it alone! Early in his memoir, Habte quotes an Eritrean proverb: “To those who have done you favors, either return the favor or tell others about their good deeds.” Habte’s memoir — Gratitude in Low Voices — is focused on gratitude to all those who helped him on his path. Along the way, he shares his experience of both rural and urban life in Eritrea, a short history of Eritrea and of the long-term conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea: “Out of the fifty-three former European colonies in Africa, Eritrea was the only country to be denied independence after its European masters departed.” His escape to Kenya is harrowing, and when he arrives in the U.S. — like many other refugees — the challenges are far from over. But I enjoyed Habte’s story. He gives brief bios of many of the people who helped him along the way as a way of honoring, which interrupts his narrative, but I respect his objective.-

Emeka Aniagolu, TesfaNews: “An excellent autobiographical work which will prove a powerful voice…for not only his family’s experience, but for his country, Eritrea.”

-

Robin Edmunds, Foreword Reviews: “This book is a reaffirmation of the good that people can do and how one young man succeeded despite the odds against him.”

-

Ann Morgan: A Year of Reading the World: “Those looking for masterful writing won’t find it here. But those looking for passion and a fresh perspective undoubtedly will.”

-

Mary Okeke, Mary Okeke Reviews: “Gratitude in Low Voices is an interesting and an uplifting narrative, simple and comprehensible, it is just Dawit telling his story.”

-

Sofia Tesfamariam, Eritrea Ministry of Information: “Dawit Ghebremichael Habte has managed to organize the memories of his journey and present a story that finds rare authenticity and validation of not just his own life but also that of others who have crossed his path… Despite beginning with an Eritrean adage, what was missing in the book was more of them.”

-

Vivian Wagner, Brevity: A Journal of Concise Literary Nonfiction: “This is, at times, a rambling and disjointed narrative… This book is a story about storytelling, about the process of creating a narrative out of disorder, and about all the people that help shape that narrative along the way.”

This is book #35 in my effort to read a book by an author from every African country in 2019.

Finding a book to read from São Tomé and Príncipe wasn’t easy. When Ann Morgan did her challenge of reading a book from every country back in 2012, she couldn’t find any literature translated into English. In the end, she crowdsourced a translation of a novel in Portuguese, Olinda Beja’s A casa do pastor (The House of the Shepherd). (Unfortunately, the translation isn’t publicly available.) I could read a book in Portuguese, but it takes me a while to read novels in Portuguese and since I’m trying to read a book from every country in one year, I’ll have to save my Portuguese reading for January. Luckily, the

Finding a book to read from São Tomé and Príncipe wasn’t easy. When Ann Morgan did her challenge of reading a book from every country back in 2012, she couldn’t find any literature translated into English. In the end, she crowdsourced a translation of a novel in Portuguese, Olinda Beja’s A casa do pastor (The House of the Shepherd). (Unfortunately, the translation isn’t publicly available.) I could read a book in Portuguese, but it takes me a while to read novels in Portuguese and since I’m trying to read a book from every country in one year, I’ll have to save my Portuguese reading for January. Luckily, the

Forbidden love! Murder for profit! Gorgeous landscapes! Shipwrecks! Passion! War! Woodworking! Nursing! Witchcraft! If this sounds like your cup of tea, then A.R. Tirant’s historical romance —

Forbidden love! Murder for profit! Gorgeous landscapes! Shipwrecks! Passion! War! Woodworking! Nursing! Witchcraft! If this sounds like your cup of tea, then A.R. Tirant’s historical romance —

A retired agent of the secret police decides to write a novel. After all, “a poor Rwandan cobbler composed a novel about the interethnic civil war in his poor African country,” and “a reformed prostitute in Saigon also wrote two brilliant novels: one about her former life when she was nobody in a dark alley, and the other about her new life after she founded a small factory that makes mint candy. Now her novels have been translated into every language, and readers are dazzled by them.” So begins Sudanese born and raised writer Amir Tag Elsir’s delightful novel,

A retired agent of the secret police decides to write a novel. After all, “a poor Rwandan cobbler composed a novel about the interethnic civil war in his poor African country,” and “a reformed prostitute in Saigon also wrote two brilliant novels: one about her former life when she was nobody in a dark alley, and the other about her new life after she founded a small factory that makes mint candy. Now her novels have been translated into every language, and readers are dazzled by them.” So begins Sudanese born and raised writer Amir Tag Elsir’s delightful novel,

At this point, there could be a whole genre of “memoirs by youth who fled war-torn African countries”: Earlier this year I read

At this point, there could be a whole genre of “memoirs by youth who fled war-torn African countries”: Earlier this year I read

The opening story of Sandra Aikaruwa Mushi’s collection of poetry and short tales,

The opening story of Sandra Aikaruwa Mushi’s collection of poetry and short tales,

An adult son has committed an unspeakable crime and narrates from his jail cell, “narrow as a tomb, and just as cold.” (The crime is so unspeakable, in fact, that it isn’t revealed until three-quarters of the way through the book.) A mother narrates from beyond the grave. In this dark novel with dual tellers, Tunisian writer Hassouna Mosbahi illustrates — in

An adult son has committed an unspeakable crime and narrates from his jail cell, “narrow as a tomb, and just as cold.” (The crime is so unspeakable, in fact, that it isn’t revealed until three-quarters of the way through the book.) A mother narrates from beyond the grave. In this dark novel with dual tellers, Tunisian writer Hassouna Mosbahi illustrates — in

As Adele boards the bus to return to her boarding school for mixed-race students in Apartheid-era Swaziland (now eSwatini), she learns that a wealthier girl has taken her place in the clique of powerful, popular girls. She suddenly finds herself rooming with Lottie, a low-income student with little respect for social norms, in a room last used by a student who died. But over the course of a school year, a series of adventures and a shared copy of the novel Jane Eyre bring the girls together. In this sweet, engaging book, Swazi born and raised writer Malla Nunn draws on her own experiences (as she discusses

As Adele boards the bus to return to her boarding school for mixed-race students in Apartheid-era Swaziland (now eSwatini), she learns that a wealthier girl has taken her place in the clique of powerful, popular girls. She suddenly finds herself rooming with Lottie, a low-income student with little respect for social norms, in a room last used by a student who died. But over the course of a school year, a series of adventures and a shared copy of the novel Jane Eyre bring the girls together. In this sweet, engaging book, Swazi born and raised writer Malla Nunn draws on her own experiences (as she discusses

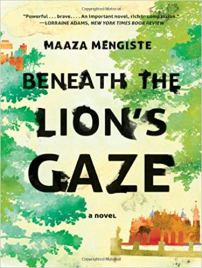

Ethiopian-born writer

Ethiopian-born writer

Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor