January was a productive month for reading! Poetry, graphic novels, prose novels, it’s all here!

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” by Zora Neale Hurston — Back in the 1930s, Hurston intervewed the last surviving person who had been brought from Africa as part of the slave trade, Cudjo Lewis. In his own vernacular, Hurston tells his story. An amazing window into a piece of African and American history.

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” by Zora Neale Hurston — Back in the 1930s, Hurston intervewed the last surviving person who had been brought from Africa as part of the slave trade, Cudjo Lewis. In his own vernacular, Hurston tells his story. An amazing window into a piece of African and American history.

Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso — Sabrina was on 7 “best graphic works of 2018” lists, more than any other book. A man’s girlfriend disappears, and an old high school friend takes the desolate man in. The deserted man spends his days listening to “Infowars”-style talk radio. The friend deals with having lost his family. It’s all dread and hopelessness. It was good but it didn’t bowl me over. (Drnaso writes in a very small font, which I find distracting.)

Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso — Sabrina was on 7 “best graphic works of 2018” lists, more than any other book. A man’s girlfriend disappears, and an old high school friend takes the desolate man in. The deserted man spends his days listening to “Infowars”-style talk radio. The friend deals with having lost his family. It’s all dread and hopelessness. It was good but it didn’t bowl me over. (Drnaso writes in a very small font, which I find distracting.)

My Boyfriend Is A Bear, by Pamela Ribon, art by Cat Farris — A twentysomething woman in a terrible job ditches the last in a series of terrible boyfriends — the sequence on previous boyfriends is hilarious — and starts dating a bear that wandered out of the mountains during the California wildfires. Can their love overcome hibernation season? And the fact that the guy is a bear? Sweeter and less weird than it sounds, but it still a little weird. Author was a screenwriter for Moana and Ralph Breaks the Internet. The art is sunny and fun. [Content: Some adult language, but that’s about it.] This from Publisher’s Weekly: “Ribon’s use of magical realism is a delight from cover to cover, as she cleverly navigates the foibles of millennial dating and friendships. Farris’s cartooning is as expressive as it is adorable, inviting the reader to share Nora and the bear’s intimacy with every panel. This resonant, absurdist modern fable is a joyful discovery.” On 2018’s “best graphic works” list.

My Boyfriend Is A Bear, by Pamela Ribon, art by Cat Farris — A twentysomething woman in a terrible job ditches the last in a series of terrible boyfriends — the sequence on previous boyfriends is hilarious — and starts dating a bear that wandered out of the mountains during the California wildfires. Can their love overcome hibernation season? And the fact that the guy is a bear? Sweeter and less weird than it sounds, but it still a little weird. Author was a screenwriter for Moana and Ralph Breaks the Internet. The art is sunny and fun. [Content: Some adult language, but that’s about it.] This from Publisher’s Weekly: “Ribon’s use of magical realism is a delight from cover to cover, as she cleverly navigates the foibles of millennial dating and friendships. Farris’s cartooning is as expressive as it is adorable, inviting the reader to share Nora and the bear’s intimacy with every panel. This resonant, absurdist modern fable is a joyful discovery.” On 2018’s “best graphic works” list.

The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After, by Clemantine Wamariya and Elizabeth Weil — Wow. Clemantine Wamariya was just six when the Rwandan genocide took place. Separated from the rest of her middle class family, she and her teenage sister Claire traverse several countries, in and out of refugee camps. Eventually they make it to the USA. The book gives a devastating portrait of how conflict and being a refugee can affect a child, and how a young woman seeks to make sense of her experience, including through literature, from Elie Wiesel to W.G. Sebald. Beautiful and gripping and thoughtful. Highly recommended. (More from me on this here.)

The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After, by Clemantine Wamariya and Elizabeth Weil — Wow. Clemantine Wamariya was just six when the Rwandan genocide took place. Separated from the rest of her middle class family, she and her teenage sister Claire traverse several countries, in and out of refugee camps. Eventually they make it to the USA. The book gives a devastating portrait of how conflict and being a refugee can affect a child, and how a young woman seeks to make sense of her experience, including through literature, from Elie Wiesel to W.G. Sebald. Beautiful and gripping and thoughtful. Highly recommended. (More from me on this here.)

Crush, by Svetlana Chmakova — This is the third book in Chmakova’s series taking place at Berrybrook Middle School, but you can read them in any order. This and the previous — Brave — are my favorites. She captures the emotion of middle school just wonderfully and introduces us to sweet and not-so-sweet kids, trying to get through the day.

Crush, by Svetlana Chmakova — This is the third book in Chmakova’s series taking place at Berrybrook Middle School, but you can read them in any order. This and the previous — Brave — are my favorites. She captures the emotion of middle school just wonderfully and introduces us to sweet and not-so-sweet kids, trying to get through the day.

Small Country, by Gaël Faye — Rwanda’s neighbor to the south, Burundi, gets far less attention but also has a deeply troubled history. Faye, born and raised in Burundi to a French father and a Rwandan refugee mother, gives a glimpse at life over the course of coups, civil war, and stealing mangos with the neighborhood boys in this autobiographical novel. Beautifully written and very evocative. (More from me on this here.)

Small Country, by Gaël Faye — Rwanda’s neighbor to the south, Burundi, gets far less attention but also has a deeply troubled history. Faye, born and raised in Burundi to a French father and a Rwandan refugee mother, gives a glimpse at life over the course of coups, civil war, and stealing mangos with the neighborhood boys in this autobiographical novel. Beautifully written and very evocative. (More from me on this here.)

Bingo Love, by Tee Franklin, illustrated by Jenn St-Onge and Joy San — This brief graphic novel tells the story of two African American women who fall in love in the 1960s but lose each other and don’t meet again for decades. Sweet, but a bit too brief to plumb the emotional depths. I was sympathetic to some (not all) of the critiques made in this review. Still, a likable story that fills a gap in representation.

Bingo Love, by Tee Franklin, illustrated by Jenn St-Onge and Joy San — This brief graphic novel tells the story of two African American women who fall in love in the 1960s but lose each other and don’t meet again for decades. Sweet, but a bit too brief to plumb the emotional depths. I was sympathetic to some (not all) of the critiques made in this review. Still, a likable story that fills a gap in representation.

China Rich Girlfriend, by Kevin Kwan (narrated by Lydia Look) — Rachel Chu finds her father! Mayhem ensues. Crazy, silly fun. Some awesomely bizarro plot twists towards the end.

China Rich Girlfriend, by Kevin Kwan (narrated by Lydia Look) — Rachel Chu finds her father! Mayhem ensues. Crazy, silly fun. Some awesomely bizarro plot twists towards the end.

When It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky, by Lesley Nneka Arimah — I listened to this book last year and loved it. I just re-listened to it and found it just excellent. Mostly realist, with an occasionally bit of fantasy sprinkled in to explore deeper truth. Arimah creates captivating worlds. (More from me on this here.)

When It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky, by Lesley Nneka Arimah — I listened to this book last year and loved it. I just re-listened to it and found it just excellent. Mostly realist, with an occasionally bit of fantasy sprinkled in to explore deeper truth. Arimah creates captivating worlds. (More from me on this here.)

When the Wanderers Come Home, by Patricia Jabbeh Wesley — Wesley returns to her homeland of Liberia and characterizes it in this collection. Beautiful, tragic reflections of the legacy of war (and lots of other stuff, too). (More from me on this here.)

When the Wanderers Come Home, by Patricia Jabbeh Wesley — Wesley returns to her homeland of Liberia and characterizes it in this collection. Beautiful, tragic reflections of the legacy of war (and lots of other stuff, too). (More from me on this here.)

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Creating Currents of Electricity and Hope, by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer (narrated by Chike Johnson) — A young man in Malawi has to drop out of secondary school for lack of funds, but with an interest in electronics, access to a library, and incredible tenacity, he builds a windmill to generate electricity for his family. True story. (More from me on this here.)

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Creating Currents of Electricity and Hope, by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer (narrated by Chike Johnson) — A young man in Malawi has to drop out of secondary school for lack of funds, but with an interest in electronics, access to a library, and incredible tenacity, he builds a windmill to generate electricity for his family. True story. (More from me on this here.)

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, by J.K. Rowling — Lockhart is a fun character, but the kids make some truly stupid choices toward the end, which lessened my enjoyment of the book.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, by J.K. Rowling — Lockhart is a fun character, but the kids make some truly stupid choices toward the end, which lessened my enjoyment of the book.

How to Be a Supervillain, by Michael Fry — Victor is the son of second-rate supervillains (maybe just villains?), who apprentice him with another supervillain. The only problem? Victor is fundamentally good. This is light and silly fun. My favorite part was all the kooky minor supervillains and superheroes that come up (as in that old movie Mystery Men). I read it with my sons.

How to Be a Supervillain, by Michael Fry — Victor is the son of second-rate supervillains (maybe just villains?), who apprentice him with another supervillain. The only problem? Victor is fundamentally good. This is light and silly fun. My favorite part was all the kooky minor supervillains and superheroes that come up (as in that old movie Mystery Men). I read it with my sons.

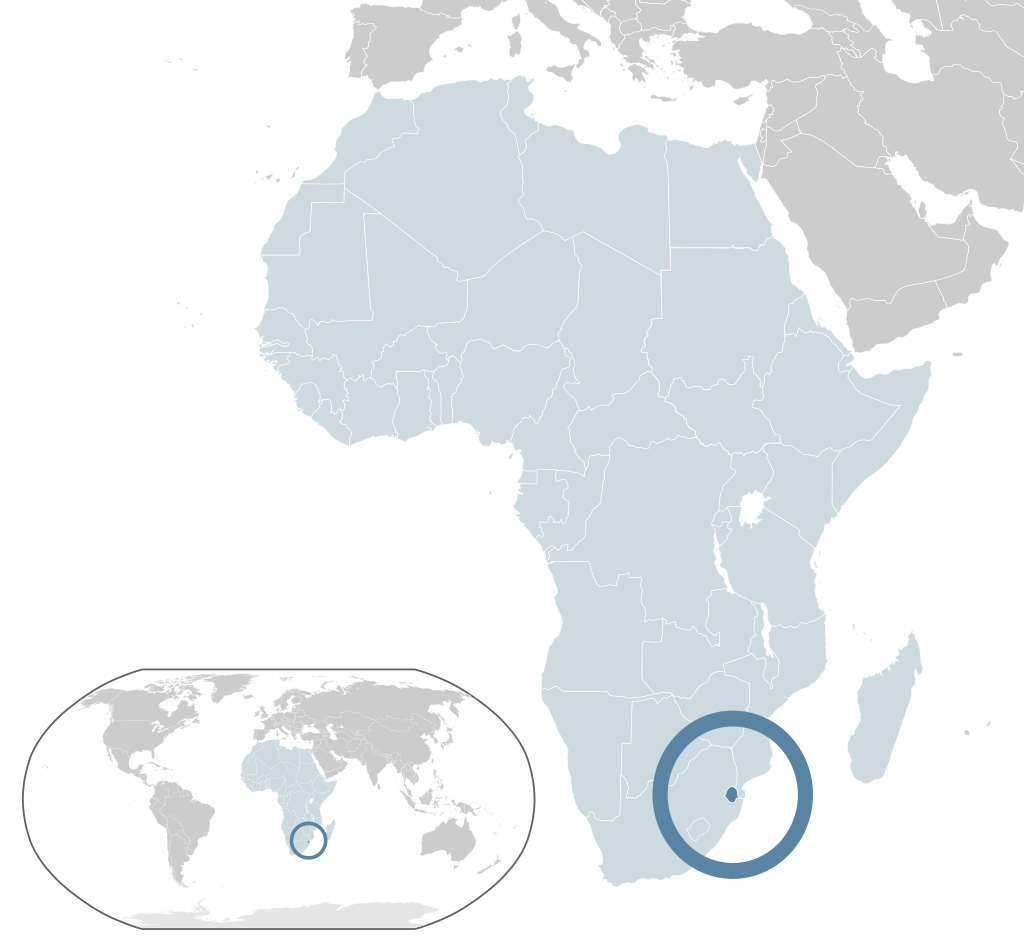

As Adele boards the bus to return to her boarding school for mixed-race students in Apartheid-era Swaziland (now eSwatini), she learns that a wealthier girl has taken her place in the clique of powerful, popular girls. She suddenly finds herself rooming with Lottie, a low-income student with little respect for social norms, in a room last used by a student who died. But over the course of a school year, a series of adventures and a shared copy of the novel Jane Eyre bring the girls together. In this sweet, engaging book, Swazi born and raised writer Malla Nunn draws on her own experiences (as she discusses

As Adele boards the bus to return to her boarding school for mixed-race students in Apartheid-era Swaziland (now eSwatini), she learns that a wealthier girl has taken her place in the clique of powerful, popular girls. She suddenly finds herself rooming with Lottie, a low-income student with little respect for social norms, in a room last used by a student who died. But over the course of a school year, a series of adventures and a shared copy of the novel Jane Eyre bring the girls together. In this sweet, engaging book, Swazi born and raised writer Malla Nunn draws on her own experiences (as she discusses

The late, great Dr. Wangarĩ Maathai has no shortage of accomplishments. Hailing from Kenya, she was the first East African woman to receive a PhD and the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. She was a professor, a politician, and an activist. In 2009, just two years before her death, she published

The late, great Dr. Wangarĩ Maathai has no shortage of accomplishments. Hailing from Kenya, she was the first East African woman to receive a PhD and the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. She was a professor, a politician, and an activist. In 2009, just two years before her death, she published

Asha Lul Mohamud Yusuf writes powerful, evocative poetry. She fled civil conflict in Somalia in 1990 and emigrated to the UK. In her brief collection (just 17 poems) —

Asha Lul Mohamud Yusuf writes powerful, evocative poetry. She fled civil conflict in Somalia in 1990 and emigrated to the UK. In her brief collection (just 17 poems) —

Welcome to a totalitarian regime with a byzantine bureaucracy that centers on one very long queue. Basma Abdel Aziz’s beautiful and maddening tale features Yehya, a man who was shot during a series of unnamed “disgraceful events.” In order to get surgery to remove the bullet — or to obtain any of a mass of services — he and thousands of others have to go and wait in line (the queue). People sleep in the queue. “Everyone expected the queue to move at any minute, and they wanted to be ready.” Yehya’s friends try to circumvent the bureaucracy, but the results are frustrating at best and violent at worst.

Welcome to a totalitarian regime with a byzantine bureaucracy that centers on one very long queue. Basma Abdel Aziz’s beautiful and maddening tale features Yehya, a man who was shot during a series of unnamed “disgraceful events.” In order to get surgery to remove the bullet — or to obtain any of a mass of services — he and thousands of others have to go and wait in line (the queue). People sleep in the queue. “Everyone expected the queue to move at any minute, and they wanted to be ready.” Yehya’s friends try to circumvent the bureaucracy, but the results are frustrating at best and violent at worst. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo Sabrina

Sabrina My Boyfriend Is A Bear

My Boyfriend Is A Bear The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After

The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After Crush

Crush Small Country

Small Country Bingo Love

Bingo Love China Rich Girlfriend

China Rich Girlfriend When It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky

When It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky When the Wanderers Come Home

When the Wanderers Come Home The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Creating Currents of Electricity and Hope

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Creating Currents of Electricity and Hope Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets How to Be a Supervillain

How to Be a Supervillain