I enjoyed lots of different kinds of books this year. Here are my top 10 plus some honorable mentions.

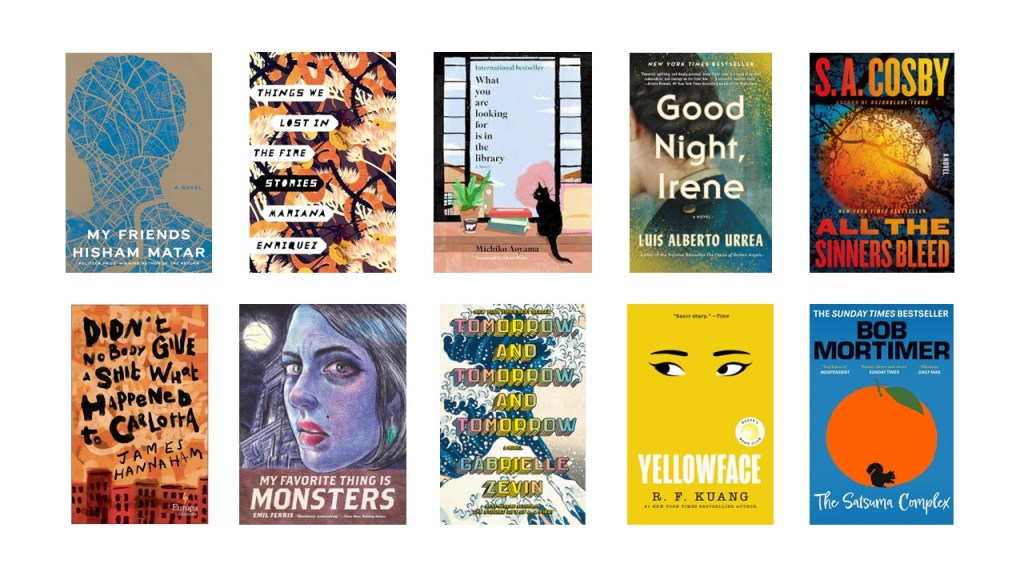

Top 10, in no particular order.

I always have trouble recommending books to people, since people are looking for very different things in books. So here’s what to find in each of my top ten.

If you don’t need a lot of plot, but you beautiful prose and deep, thoughtful reflections on friendship, exile, literature, and life, I recommend Hisham Matar’s My Friends. I listened to this one slowly, chewing on each chapter. I liked it even more than Matar’s memoir, The Return, which I also enjoyed.

If you seek a beautiful, gentle book about people who seem to be stuck in their lives learning how to move forward, I recommend Michiko Aoyama’s What You Are Looking For Is In the Library (translated by Alison Watts). That description sounds schmaltzy, but it really isn’t. I found it very moving.

Horror is not a genre of literature that generally draws me, but Mariana Enriquez’s short story collection Things We Lost in the Fire (translated by Megan McDowell) is a powerful reminder of how horror can shine a light on social ills. I wrote this in my longer review: “In almost every story, I found myself both engaged in the plot and the characters but also asking myself, What is this telling me about violence? about gender? about poverty? about class? about connection?” I also listened to this book in Spanish, Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego, and the Enriquez’s original wordplay is even better. I especially enjoyed the stories “Spider Web,” “Adela’s House,” and “The Neighbor’s Courtyard.”

Before reading Luis Alberto Urrea’s novel Good Night, Irene, I’d never heard of the “clubmobiles,” a mobile service during World War II. But this deeply researched (the author’s note at the end is first class) and moving novel about women serving in a largely forgotten capacity during the war is wonderful. It brought me to tears.

If you’re up for some very dark comedy, James Hannaham’s Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta invites us into the company of an Afro-Colombian trans-woman as she spends her first weekend out of prison. With flashbacks to her time in prison, there is some tough stuff here. But Carlotta is an amazing protagonist. The audiobook, read by Hannaham as well as Flame Munroe, is an excellent performance.

If you like a thriller, S.A. Cosby’s All the Sinners Bleed, about an African-American sheriff trying to stop a serial killer in a southern Virginia town is top notch. Lots of excitement, lots of race drama, plus meditations on faith and references to Yeats and Shakespeare.

If you’re up for cringe comedy, R. F. Kuang’s Yellowface is a hilarious takedown of the publishing industry. A character vaguely presents as Asian to sell a book that she stole from her deceased friend. I couldn’t stop listening to this protagonist making bad decision after bad decision.

If you want to follow a trio of friends over decades, try Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, about video game designers pushing the boundaries of design and friendship. It’s a moving story; I didn’t think the ending was as strong as the start and middle, but I was thoroughly engaged. I have no interest in video games, but Zevin made me care.

If you want pure, silly fun in the form of a surreal thriller, I recommend Bob Mortimer’s The Satsuma Complex. The audiobook (read by Mortimer and Sally Phillips) is absolutely hilarious. A legal assistant gets mixed up in intrigue, there’s a talk squirrel, the cast of characters is wacky and wild. Funnest book I read this year.

And the one re-read (and the one graphic novel) in my top ten is My Favorite Thing Is Monsters: Volume 1. From my longer review: “This is a dark coming-of-age tale: ten-year-old Karen Reyes (living in 1960s Chicago) experiences traumas that no child should have to, even as she learns of the intense traumas of others while trying to solve the mystery of her murdered neighbor. She processes some of her experiences and feelings and identity by identifying with … monsters: she disguises herself as a monster, and every few pages of this graphic notebook fictional memoir is the cover of a horror comic book. Anyway, my review is all over the place in part because the book is so FULL: the feelings and the art and the characters and the action and the plot. The Holocaust, queer identity, civil rights, class divides. It’s all here, and it all somehow hangs together. I’ve never read a graphic novel like this one.” (And I’ve read a few.)

In addition to my ten best, I’ll add six honorable mentions:

- Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, by Ruth Franklin. “I read this biography in tandem with other of Jackson’s work: a short story collection (Dark Tales) and a graphic adaptation of her most famous story (Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”: The Authorized Graphic Adaptation). A year or so ago I read one of Jackson’s two most famous novels, The Haunting of Hill House. I think that this biography will be most enjoyed with a familiarity with Jackson’s work. But Franklin is a skilled chronicler and I’m excited to read more of her work” (from my longer review).

- Teen Couple Have Fun Outdoors, by Aravind Jayan. “In Trivandrum, a city in Kerala, India, a couple of college kids are fooling around in a secluded spot, and—unbeknownst to them—they’re being filmed. Later, the footage makes its way to a pornographic website, local people start discovering the video, and everything goes pear-shaped. This might sound like a spicy novel, but it’s not at all (besides a brief, oblique description of the video). Rather, it’s a fascinating exploration of intergenerational dynamics, of siblings mediating between parents and other siblings, of how (to quote Tolstoy) ‘each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way'” (from my longer review).

- The Song of Achilles, by Madeline Miller. A beautifully written retelling of the story of Achilles, told by his companion Patroclus.

- American Zion: A New History of Mormonism, by Benjamin Park. This is the single volume history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that I’d most recommend. Lots of representation of underrepresented groups. Lots of focus on how conflict within the organization led to changes. I learned a lot (and I’ve read a bit in this space).

- Anansi’s Gold: The Man Who Looted the West, Outfoxed Washington, and Swindled the World, by Yepoka Yeebo. This intertwines the story of a very long con by a Ghanaian man with the post-independence history of Ghana. Both strands are fascinating. It took me a while to get into it but ultimately pretty awesome.

- The Magician’s Nephew, by C.S. Lewis (audiobook narrated by Kenneth Branagh). This is my favorite of the Narnia books, and Branagh’s narration is great.

Happy reading in 2025!